forest rights, conservation and dilemmas of growth

forest rights, conservation and dilemmas of growth

© mazoomdaar 2011

© mazoomdaar 2011

Home | Reports | Related Articles | Resources | Gallery | Feedback | Contact | About

Cat Among The People

Snow leopards share a particularly punishing habitat with people in the higher reaches of the Himalayas, with resources

scarce and vegetation sparse. The conventional conservation model of separating wild animals and people simply does

not work here. India's green establishment is showing signs of accepting this reality, if only grudgingly

Jay Mazoomdaar | 30 July, 2010 | OPEN

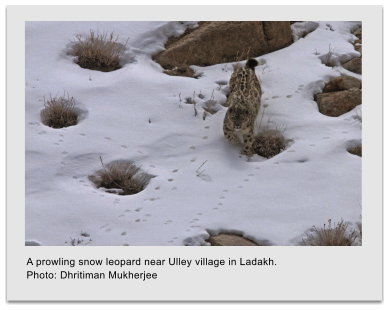

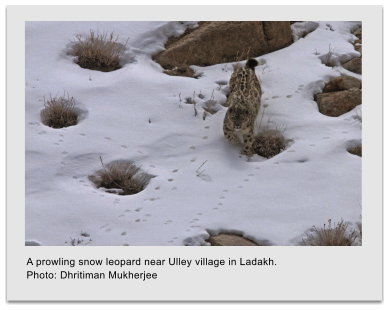

So you know they are called 'ghosts of the mountain'. Rarely

spotted (they are as good as camouflage artists ever get), never

heard (the only one that ever roared was Tai Lung in Kung Fu

Panda, but then he was also nasty) and barely understood (few

behavioural studies have been attempted), they exist in smaller

numbers in India than even tigers.

But this is really not just about the most mysterious if not

charismatic of all big cats-snow leopards.

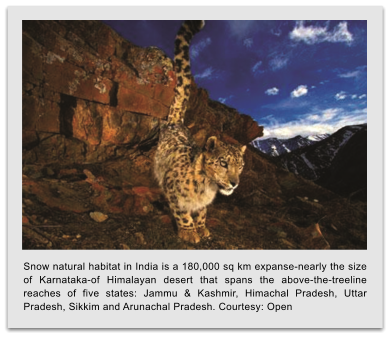

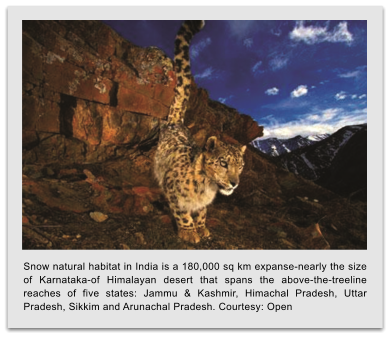

What you probably do not know is that the cat's natural habitat in

India is a 180,000 sq km expanse-nearly the size of Karnataka-of

Himalayan desert that spans the above-the-treeline reaches of five

states: Jammu & Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh,

Sikkim and Arunachal Pradesh. Cold and arid, this region is the

source of most north Indian rivers.

And yet, such a vast and critical expanse has rarely drawn the

attention of India's conservation establishment. On paper, there

exist more than two dozen Protected Areas (PAs)-sanctuaries and national parks-in this region, covering 32,000 sq km, a figure that

equals the combined area of all tiger reserves put together. But in terms of funds, staff and management, these high-altitude PAs are

mere markings on a map.

Things were worse in the early 1990s, when, as a young student of the Wildlife Institute of India (WII), Yash Veer Bhatnagar began

studying snow leopards and their species of prey. With sundry forest departments struggling to fill up field staff vacancies in the best of

India's tiger reserves, snow leopards had little hope of being watched over in places far less hospitable to humans. But as Bhatnagar

kept tracing the animal's tracks along Spiti's snow ridges, he grew increasingly restless thinking up a workable conservation strategy

that was proving to be as elusive as the big cat itself.

Nearly two decades on, Dr Bhatnagar and his associates would help shape Project Snow Leopard, a species recovery programme with an

innovative plan drafted in 2008 that could, with luck, save the species from extinction.

Dr Bhatnagar was not alone. His senior at the WII, Dr Raghu

Chundawat, having studied wildlife in the cold deserts of J&K since

the late 1980s, had already reported a startling fact: more than half

his subjects in Ladakh, including snow leopards, were found outside

the PAs. "There are a number of ecological factors behind this,"

explains Dr Chundawat, "sparse resources, extreme climatic

conditions, seasonal migration of prey species, etcetera, make the

cat very mobile across large ranges."

As for other efforts, in 1996, Dr Charudutt Mishra, another WII

alumnus and a snow leopard expert himself, had set up the Mysore-

based Nature Conservation Foundation (NCF) with a group of young

biologists. It had some valuable field experience to offer, too.

It was Dr Chundawat's work, however, that gave Project Snow

Leopard its broad direction. "Raghu's was a fantastic study and got

us thinking: 'If 80 per cent of Ladakh had wildlife value, how would

securing a few PAs help conservation?'" recalls Dr Bhatnagar.

The question still stands. Spiti in Himachal Pradesh is significant in terms of snow leopard presence, for example, but notifying all of

Spiti or Ladakh as a PA would not only be a logistical nightmare, given the difficulty in managing the existing PAs, but also defeat the

purpose of conservation on at least two counts.

First, the experience in other snow leopard-range countries shows that merely declaring vast areas as PAs does not help. In Central

Asia, for example, Tibet's Changthang Wildlife Preserve extends over 500,000 sq km, but organised hunting remains a serious threat in

most parts; the picture is not very different in Mongolia or Afghanistan.

Second, resources are extremely scarce at high altitudes; like the wildlife there, people must use every bit of land they can access at

those Himalayan heights. The conventional model of PA-based conservation demands the securing of inviolate spaces for wildlife. But,

in a cold desert, displacing people from existing PAs, leave alone notifying larger ones, amounts to threatening their survival. Besides,

can anything justify evicting people from PAs if wildlife is seen to coexist with people in non-PA areas?

But ten years ago, coexistence was too radical an idea to explore for much of India's conservation establishment.

In the absence of effective protection, what snow leopards once had

going for them was a sparse local population in the upper reaches of

the Himalayas (less than a person per sq km). In the past two

decades or so, however, even those heights have been witness to

'development' in the form of roads, dam projects and the like. The

most active government agency has been the military, busy

defending the country's borders, and, in the process, slicing and

dicing the region with impenetrable fences and encampments. All

this has also meant a labour influx, with whom indigenous

populations (and their livestock) now compete for natural

resources. This has meant overgrazing, and the competition for

resources has led to a loss of wild prey for snow leopards. And with

the big cats increasingly turning on livestock, they often face human

retaliation. Organised poaching has been a reality even here.

Clear that exclusive sanctuaries for snow leopards were not a

feasible idea, Bhatnagar and his colleagues focused on

understanding the cat and engaging with villagers and the local forest staff to figure out a conservation solution.

In 2001, the NCF's Mishra had done some groundwork in Spiti's Kibber Wildlife Sanctuary. Human communities, he found, could be

negotiated with to leave wildlife pastures untouched. To look after this area, a few villagers could be hired-picked by locals from among

themselves. This model has been in operation in Spiti for several years now, and so far, over 15 sq km has been freed of livestock grazing

around Kibber, and the population of bharals (blue sheep), staple prey for snow leopards, has almost trebled since.

Another coexistence success has been Ladakh's 3,000 sq km Hemis National Park, which is home to around 100 families that live in 17

small villages within it. Their relocation was impossible without subjecting them to destitution, since all the other land of Ladakh was

already occupied by either monasteries or local communities. Today, despite the human presence, Hemis has one of the country's

highest snow leopard densities. The park's villagers, urged by the Snow Leopard Conservancy India Trust (SLC-IT), an NGO, regulate

livestock grazing in pastures used by small Tibetan argali (a prime prey species for snow leopards). According to Radhika Kothari of

SLC-IT, this was achieved by the NGO in coordination with the forest department. They launched a sustained awareness drive and

offered families incentives such as home-stay tourism and improved corrals for the protection of their livestock.

The basic strategy of engaging local communities remains simple: help protect livestock (by ensuring better herding methods,

constructing corrals, offering vaccinations and so on), compensate for losses (via insurance, for example), create income opportunities

(community tourism, handicrafts, etcetera), restore traditional values of tolerance towards wildlife, and promote ecological awareness.

This story repeats itself in other range countries; livestock insurance and micro-credit schemes are big successes in Mongolia,

handicraft in Kyrgyzstan, and livestock vaccination in Pakistan.

Encouraged by early success stories in engaging local communities in J&K and Himachal, the NCF backed a conservation model in the

context of the three-decade-old Sloss debate (single large or several small, that is). "The idea of wildlife 'islands' surrounded by a 'sea'

of people does not work in high-altitude areas, where wildlife presence is almost continuous," explains Dr Bhatnagar, "Instead,

communities can voluntarily secure many small patches of very high wildlife value-small cores or breeding grounds spanning 10-100 sq

km each-if they have the incentive of escaping exclusionary laws across larger areas [big PAs]."

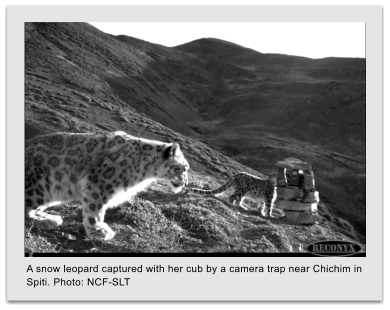

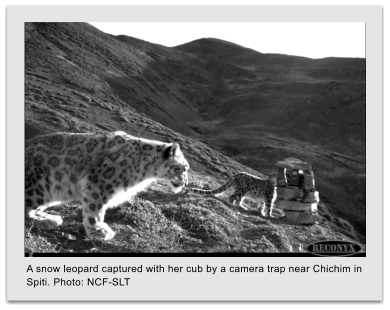

The NCF has identified 15 'small cores' in Spiti, of which three (at Kibber WLS, near Lossar, and near Chichim) have already been

secured through the foundation's efforts with locals. In Ladakh, too, village elders and the Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development

Council (LAHDC) agreed to stop grazing activities in seven side-valleys seen to be of high wildlife value-in exchange for assured

community access to the rest of the Hemis National Park. It's a win-win deal.

The experience of other snow leopard range countries supports the

conclusion that sparse human presence does not affect this wild

cat's well-being. A soon-to-be published report on Mongolia by the

Seattle-based Snow Leopard Trust (SLT) indicates that the presence

or absence of nomadic herders around snow leopards inside as well

as outside PAs in the South Gobi Desert does not affect the

probability of snow leopards using a particular site.

Complementarily, there is no record anywhere in the world of a

human death due to a snow leopard attack.

So, by the time Project Snow Leopard drew up its plan in 2008, a

diverse team of officials and experts from the Union Ministry of

Environment & Forests, WII, WWF and NCF-SLT, apart from five

snow leopard states, had come to agree that 'given the widespread

occurrence of wildlife on common land, and the continued

traditional land use within PAs, wildlife management in the region

needs to be made participatory both within and outside PAs'.

More than one-third of the project budget (at least 3 per cent of the Ministry's total outlay) was earmarked for facilitating a 'landscape-

level approach', rationalising 'the existing PA network' and developing 'a framework for wildlife conservation outside PAs'.

Each of the five states was supposed to select a Project Snow Leopard site, a combination of PA and non-PA areas, within a year and set

up a state-level snow leopard conservation society with community participation. However, given the slow pace at which governments

function, not much has moved since, except in Himachal Pradesh, where the state forest department has set up a participatory

management plan for over half of Spiti wildlife division.

The red tape apart, two other factors are threatening to thwart this unique conservation project: the reluctance of the Ministry to

release funds to non-PAs, and the indifference of some state forest departments towards a management plan for areas outside

sanctuaries and national parks (such a plan must be submitted). "Snow leopards are present in many areas outside PAs, and I have

asked for proposals from all high-altitude divisions. But there is no response from the non-wildlife divisions yet. It's probably a mindset

issue," sighs Srikant Chandola, chief wildlife warden, Uttarakhand.

Perhaps the same mindset prompted a 2010 WWF-India report to recommend only PAs in Uttarakhand as potential sites for snow

leopard conservation, though the author Aishwarya Maheshwari now agrees that a landscape approach, "as mentioned in Project Snow

Leopard", is necessary.

Jagdish Kishwan, additional director-general (wildlife) at the Ministry, says that the Centre is keen to invest money in non-PAs, but

there are "some technical issues"; moreover, the Ministry's meagre allocation might end up too thinly spread in doing so.

The Ministry has its own grand recovery plan. Announced almost simultaneously with Project Snow Leopard, it has an ambitious Rs

800 crore scheme, Integrated Development of Wildlife Habitats (IDWH), aimed at the recovery of 15 key species including ones found

mostly outside PAs, such as: snow leopards, great Indian bustards and vultures. Centrally sponsored, IDWH has earmarked Rs 250

crore for 'protection of wildlife outside PAs'. The states have been asked to submit their Project Snow Leopard management plans under

the IDWH aegis.

If that is the case, what stops the Ministry from releasing money for non-PAs? "India's 650-odd PAs are our priority. But I agree that

certain key species need support outside PAs. We are examining these issues. The Government will find a way to provide funds to non-

wildlife divisions under Project Snow Leopard," assures Kishwan.

Going by the original 2008 document outlining the plan, Project Snow Leopard should have been in its second year of implementation

by now.

That it hasn't yet hit the ground, let's hope, is not a sign of apathy towards a big cat that has had-for no fault of its own-only a ghostly

presence in the consciousness of the establishment.

The author is an independent journalist

Cat Among The People

Snow leopards share a particularly punishing habitat with people in the higher reaches of the Himalayas, with resources

scarce and vegetation sparse. The conventional conservation model of separating wild animals and people simply does

not work here. India's green establishment is showing signs of accepting this reality, if only grudgingly

Jay Mazoomdaar | 30 July, 2010 | OPEN

So you know they are called 'ghosts of the mountain'. Rarely

spotted (they are as good as camouflage artists ever get), never

heard (the only one that ever roared was Tai Lung in Kung Fu

Panda, but then he was also nasty) and barely understood (few

behavioural studies have been attempted), they exist in smaller

numbers in India than even tigers.

But this is really not just about the most mysterious if not

charismatic of all big cats-snow leopards.

What you probably do not know is that the cat's natural habitat in

India is a 180,000 sq km expanse-nearly the size of Karnataka-of

Himalayan desert that spans the above-the-treeline reaches of five

states: Jammu & Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh,

Sikkim and Arunachal Pradesh. Cold and arid, this region is the

source of most north Indian rivers.

And yet, such a vast and critical expanse has rarely drawn the

attention of India's conservation establishment. On paper, there

exist more than two dozen Protected Areas (PAs)-sanctuaries and national parks-in this region, covering 32,000 sq km, a figure that

equals the combined area of all tiger reserves put together. But in terms of funds, staff and management, these high-altitude PAs are

mere markings on a map.

Things were worse in the early 1990s, when, as a young student of the Wildlife Institute of India (WII), Yash Veer Bhatnagar began

studying snow leopards and their species of prey. With sundry forest departments struggling to fill up field staff vacancies in the best of

India's tiger reserves, snow leopards had little hope of being watched over in places far less hospitable to humans. But as Bhatnagar

kept tracing the animal's tracks along Spiti's snow ridges, he grew increasingly restless thinking up a workable conservation strategy

that was proving to be as elusive as the big cat itself.

Nearly two decades on, Dr Bhatnagar and his associates would help shape Project Snow Leopard, a species recovery programme with an

innovative plan drafted in 2008 that could, with luck, save the species from extinction.

Dr Bhatnagar was not alone. His senior at the WII, Dr Raghu

Chundawat, having studied wildlife in the cold deserts of J&K since

the late 1980s, had already reported a startling fact: more than half

his subjects in Ladakh, including snow leopards, were found outside

the PAs. "There are a number of ecological factors behind this,"

explains Dr Chundawat, "sparse resources, extreme climatic

conditions, seasonal migration of prey species, etcetera, make the

cat very mobile across large ranges."

As for other efforts, in 1996, Dr Charudutt Mishra, another WII

alumnus and a snow leopard expert himself, had set up the Mysore-

based Nature Conservation Foundation (NCF) with a group of young

biologists. It had some valuable field experience to offer, too.

It was Dr Chundawat's work, however, that gave Project Snow

Leopard its broad direction. "Raghu's was a fantastic study and got

us thinking: 'If 80 per cent of Ladakh had wildlife value, how would

securing a few PAs help conservation?'" recalls Dr Bhatnagar.

The question still stands. Spiti in Himachal Pradesh is significant in terms of snow leopard presence, for example, but notifying all of

Spiti or Ladakh as a PA would not only be a logistical nightmare, given the difficulty in managing the existing PAs, but also defeat the

purpose of conservation on at least two counts.

First, the experience in other snow leopard-range countries shows that merely declaring vast areas as PAs does not help. In Central

Asia, for example, Tibet's Changthang Wildlife Preserve extends over 500,000 sq km, but organised hunting remains a serious threat in

most parts; the picture is not very different in Mongolia or Afghanistan.

Second, resources are extremely scarce at high altitudes; like the wildlife there, people must use every bit of land they can access at

those Himalayan heights. The conventional model of PA-based conservation demands the securing of inviolate spaces for wildlife. But,

in a cold desert, displacing people from existing PAs, leave alone notifying larger ones, amounts to threatening their survival. Besides,

can anything justify evicting people from PAs if wildlife is seen to coexist with people in non-PA areas?

But ten years ago, coexistence was too radical an idea to explore for much of India's conservation establishment.

In the absence of effective protection, what snow leopards once had

going for them was a sparse local population in the upper reaches of

the Himalayas (less than a person per sq km). In the past two

decades or so, however, even those heights have been witness to

'development' in the form of roads, dam projects and the like. The

most active government agency has been the military, busy

defending the country's borders, and, in the process, slicing and

dicing the region with impenetrable fences and encampments. All

this has also meant a labour influx, with whom indigenous

populations (and their livestock) now compete for natural

resources. This has meant overgrazing, and the competition for

resources has led to a loss of wild prey for snow leopards. And with

the big cats increasingly turning on livestock, they often face human

retaliation. Organised poaching has been a reality even here.

Clear that exclusive sanctuaries for snow leopards were not a

feasible idea, Bhatnagar and his colleagues focused on

understanding the cat and engaging with villagers and the local forest staff to figure out a conservation solution.

In 2001, the NCF's Mishra had done some groundwork in Spiti's Kibber Wildlife Sanctuary. Human communities, he found, could be

negotiated with to leave wildlife pastures untouched. To look after this area, a few villagers could be hired-picked by locals from among

themselves. This model has been in operation in Spiti for several years now, and so far, over 15 sq km has been freed of livestock grazing

around Kibber, and the population of bharals (blue sheep), staple prey for snow leopards, has almost trebled since.

Another coexistence success has been Ladakh's 3,000 sq km Hemis National Park, which is home to around 100 families that live in 17

small villages within it. Their relocation was impossible without subjecting them to destitution, since all the other land of Ladakh was

already occupied by either monasteries or local communities. Today, despite the human presence, Hemis has one of the country's

highest snow leopard densities. The park's villagers, urged by the Snow Leopard Conservancy India Trust (SLC-IT), an NGO, regulate

livestock grazing in pastures used by small Tibetan argali (a prime prey species for snow leopards). According to Radhika Kothari of

SLC-IT, this was achieved by the NGO in coordination with the forest department. They launched a sustained awareness drive and

offered families incentives such as home-stay tourism and improved corrals for the protection of their livestock.

The basic strategy of engaging local communities remains simple: help protect livestock (by ensuring better herding methods,

constructing corrals, offering vaccinations and so on), compensate for losses (via insurance, for example), create income opportunities

(community tourism, handicrafts, etcetera), restore traditional values of tolerance towards wildlife, and promote ecological awareness.

This story repeats itself in other range countries; livestock insurance and micro-credit schemes are big successes in Mongolia,

handicraft in Kyrgyzstan, and livestock vaccination in Pakistan.

Encouraged by early success stories in engaging local communities in J&K and Himachal, the NCF backed a conservation model in the

context of the three-decade-old Sloss debate (single large or several small, that is). "The idea of wildlife 'islands' surrounded by a 'sea'

of people does not work in high-altitude areas, where wildlife presence is almost continuous," explains Dr Bhatnagar, "Instead,

communities can voluntarily secure many small patches of very high wildlife value-small cores or breeding grounds spanning 10-100 sq

km each-if they have the incentive of escaping exclusionary laws across larger areas [big PAs]."

The NCF has identified 15 'small cores' in Spiti, of which three (at Kibber WLS, near Lossar, and near Chichim) have already been

secured through the foundation's efforts with locals. In Ladakh, too, village elders and the Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development

Council (LAHDC) agreed to stop grazing activities in seven side-valleys seen to be of high wildlife value-in exchange for assured

community access to the rest of the Hemis National Park. It's a win-win deal.

The experience of other snow leopard range countries supports the

conclusion that sparse human presence does not affect this wild

cat's well-being. A soon-to-be published report on Mongolia by the

Seattle-based Snow Leopard Trust (SLT) indicates that the presence

or absence of nomadic herders around snow leopards inside as well

as outside PAs in the South Gobi Desert does not affect the

probability of snow leopards using a particular site.

Complementarily, there is no record anywhere in the world of a

human death due to a snow leopard attack.

So, by the time Project Snow Leopard drew up its plan in 2008, a

diverse team of officials and experts from the Union Ministry of

Environment & Forests, WII, WWF and NCF-SLT, apart from five

snow leopard states, had come to agree that 'given the widespread

occurrence of wildlife on common land, and the continued

traditional land use within PAs, wildlife management in the region

needs to be made participatory both within and outside PAs'.

More than one-third of the project budget (at least 3 per cent of the Ministry's total outlay) was earmarked for facilitating a 'landscape-

level approach', rationalising 'the existing PA network' and developing 'a framework for wildlife conservation outside PAs'.

Each of the five states was supposed to select a Project Snow Leopard site, a combination of PA and non-PA areas, within a year and set

up a state-level snow leopard conservation society with community participation. However, given the slow pace at which governments

function, not much has moved since, except in Himachal Pradesh, where the state forest department has set up a participatory

management plan for over half of Spiti wildlife division.

The red tape apart, two other factors are threatening to thwart this unique conservation project: the reluctance of the Ministry to

release funds to non-PAs, and the indifference of some state forest departments towards a management plan for areas outside

sanctuaries and national parks (such a plan must be submitted). "Snow leopards are present in many areas outside PAs, and I have

asked for proposals from all high-altitude divisions. But there is no response from the non-wildlife divisions yet. It's probably a mindset

issue," sighs Srikant Chandola, chief wildlife warden, Uttarakhand.

Perhaps the same mindset prompted a 2010 WWF-India report to recommend only PAs in Uttarakhand as potential sites for snow

leopard conservation, though the author Aishwarya Maheshwari now agrees that a landscape approach, "as mentioned in Project Snow

Leopard", is necessary.

Jagdish Kishwan, additional director-general (wildlife) at the Ministry, says that the Centre is keen to invest money in non-PAs, but

there are "some technical issues"; moreover, the Ministry's meagre allocation might end up too thinly spread in doing so.

The Ministry has its own grand recovery plan. Announced almost simultaneously with Project Snow Leopard, it has an ambitious Rs

800 crore scheme, Integrated Development of Wildlife Habitats (IDWH), aimed at the recovery of 15 key species including ones found

mostly outside PAs, such as: snow leopards, great Indian bustards and vultures. Centrally sponsored, IDWH has earmarked Rs 250

crore for 'protection of wildlife outside PAs'. The states have been asked to submit their Project Snow Leopard management plans under

the IDWH aegis.

If that is the case, what stops the Ministry from releasing money for non-PAs? "India's 650-odd PAs are our priority. But I agree that

certain key species need support outside PAs. We are examining these issues. The Government will find a way to provide funds to non-

wildlife divisions under Project Snow Leopard," assures Kishwan.

Going by the original 2008 document outlining the plan, Project Snow Leopard should have been in its second year of implementation

by now.

That it hasn't yet hit the ground, let's hope, is not a sign of apathy towards a big cat that has had-for no fault of its own-only a ghostly

presence in the consciousness of the establishment.

The author is an independent journalist

Cat Among The People

Snow leopards share a particularly punishing habitat with people in the higher reaches of the Himalayas, with resources

scarce and vegetation sparse. The conventional conservation model of separating wild animals and people simply does

not work here. India's green establishment is showing signs of accepting this reality, if only grudgingly

Jay Mazoomdaar | 30 July, 2010 | OPEN

So you know they are called 'ghosts of the mountain'. Rarely

spotted (they are as good as camouflage artists ever get), never

heard (the only one that ever roared was Tai Lung in Kung Fu

Panda, but then he was also nasty) and barely understood (few

behavioural studies have been attempted), they exist in smaller

numbers in India than even tigers.

But this is really not just about the most mysterious if not

charismatic of all big cats-snow leopards.

What you probably do not know is that the cat's natural habitat in

India is a 180,000 sq km expanse-nearly the size of Karnataka-of

Himalayan desert that spans the above-the-treeline reaches of five

states: Jammu & Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh,

Sikkim and Arunachal Pradesh. Cold and arid, this region is the

source of most north Indian rivers.

And yet, such a vast and critical expanse has rarely drawn the

attention of India's conservation establishment. On paper, there

exist more than two dozen Protected Areas (PAs)-sanctuaries and national parks-in this region, covering 32,000 sq km, a figure that

equals the combined area of all tiger reserves put together. But in terms of funds, staff and management, these high-altitude PAs are

mere markings on a map.

Things were worse in the early 1990s, when, as a young student of the Wildlife Institute of India (WII), Yash Veer Bhatnagar began

studying snow leopards and their species of prey. With sundry forest departments struggling to fill up field staff vacancies in the best of

India's tiger reserves, snow leopards had little hope of being watched over in places far less hospitable to humans. But as Bhatnagar

kept tracing the animal's tracks along Spiti's snow ridges, he grew increasingly restless thinking up a workable conservation strategy

that was proving to be as elusive as the big cat itself.

Nearly two decades on, Dr Bhatnagar and his associates would help shape Project Snow Leopard, a species recovery programme with an

innovative plan drafted in 2008 that could, with luck, save the species from extinction.

Dr Bhatnagar was not alone. His senior at the WII, Dr Raghu

Chundawat, having studied wildlife in the cold deserts of J&K since

the late 1980s, had already reported a startling fact: more than half

his subjects in Ladakh, including snow leopards, were found outside

the PAs. "There are a number of ecological factors behind this,"

explains Dr Chundawat, "sparse resources, extreme climatic

conditions, seasonal migration of prey species, etcetera, make the

cat very mobile across large ranges."

As for other efforts, in 1996, Dr Charudutt Mishra, another WII

alumnus and a snow leopard expert himself, had set up the Mysore-

based Nature Conservation Foundation (NCF) with a group of young

biologists. It had some valuable field experience to offer, too.

It was Dr Chundawat's work, however, that gave Project Snow

Leopard its broad direction. "Raghu's was a fantastic study and got

us thinking: 'If 80 per cent of Ladakh had wildlife value, how would

securing a few PAs help conservation?'" recalls Dr Bhatnagar.

The question still stands. Spiti in Himachal Pradesh is significant in terms of snow leopard presence, for example, but notifying all of

Spiti or Ladakh as a PA would not only be a logistical nightmare, given the difficulty in managing the existing PAs, but also defeat the

purpose of conservation on at least two counts.

First, the experience in other snow leopard-range countries shows that merely declaring vast areas as PAs does not help. In Central

Asia, for example, Tibet's Changthang Wildlife Preserve extends over 500,000 sq km, but organised hunting remains a serious threat in

most parts; the picture is not very different in Mongolia or Afghanistan.

Second, resources are extremely scarce at high altitudes; like the wildlife there, people must use every bit of land they can access at

those Himalayan heights. The conventional model of PA-based conservation demands the securing of inviolate spaces for wildlife. But,

in a cold desert, displacing people from existing PAs, leave alone notifying larger ones, amounts to threatening their survival. Besides,

can anything justify evicting people from PAs if wildlife is seen to coexist with people in non-PA areas?

But ten years ago, coexistence was too radical an idea to explore for much of India's conservation establishment.

In the absence of effective protection, what snow leopards once had

going for them was a sparse local population in the upper reaches of

the Himalayas (less than a person per sq km). In the past two

decades or so, however, even those heights have been witness to

'development' in the form of roads, dam projects and the like. The

most active government agency has been the military, busy

defending the country's borders, and, in the process, slicing and

dicing the region with impenetrable fences and encampments. All

this has also meant a labour influx, with whom indigenous

populations (and their livestock) now compete for natural

resources. This has meant overgrazing, and the competition for

resources has led to a loss of wild prey for snow leopards. And with

the big cats increasingly turning on livestock, they often face human

retaliation. Organised poaching has been a reality even here.

Clear that exclusive sanctuaries for snow leopards were not a

feasible idea, Bhatnagar and his colleagues focused on

understanding the cat and engaging with villagers and the local forest staff to figure out a conservation solution.

In 2001, the NCF's Mishra had done some groundwork in Spiti's Kibber Wildlife Sanctuary. Human communities, he found, could be

negotiated with to leave wildlife pastures untouched. To look after this area, a few villagers could be hired-picked by locals from among

themselves. This model has been in operation in Spiti for several years now, and so far, over 15 sq km has been freed of livestock grazing

around Kibber, and the population of bharals (blue sheep), staple prey for snow leopards, has almost trebled since.

Another coexistence success has been Ladakh's 3,000 sq km Hemis National Park, which is home to around 100 families that live in 17

small villages within it. Their relocation was impossible without subjecting them to destitution, since all the other land of Ladakh was

already occupied by either monasteries or local communities. Today, despite the human presence, Hemis has one of the country's

highest snow leopard densities. The park's villagers, urged by the Snow Leopard Conservancy India Trust (SLC-IT), an NGO, regulate

livestock grazing in pastures used by small Tibetan argali (a prime prey species for snow leopards). According to Radhika Kothari of

SLC-IT, this was achieved by the NGO in coordination with the forest department. They launched a sustained awareness drive and

offered families incentives such as home-stay tourism and improved corrals for the protection of their livestock.

The basic strategy of engaging local communities remains simple: help protect livestock (by ensuring better herding methods,

constructing corrals, offering vaccinations and so on), compensate for losses (via insurance, for example), create income opportunities

(community tourism, handicrafts, etcetera), restore traditional values of tolerance towards wildlife, and promote ecological awareness.

This story repeats itself in other range countries; livestock insurance and micro-credit schemes are big successes in Mongolia,

handicraft in Kyrgyzstan, and livestock vaccination in Pakistan.

Encouraged by early success stories in engaging local communities in J&K and Himachal, the NCF backed a conservation model in the

context of the three-decade-old Sloss debate (single large or several small, that is). "The idea of wildlife 'islands' surrounded by a 'sea'

of people does not work in high-altitude areas, where wildlife presence is almost continuous," explains Dr Bhatnagar, "Instead,

communities can voluntarily secure many small patches of very high wildlife value-small cores or breeding grounds spanning 10-100 sq

km each-if they have the incentive of escaping exclusionary laws across larger areas [big PAs]."

The NCF has identified 15 'small cores' in Spiti, of which three (at Kibber WLS, near Lossar, and near Chichim) have already been

secured through the foundation's efforts with locals. In Ladakh, too, village elders and the Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development

Council (LAHDC) agreed to stop grazing activities in seven side-valleys seen to be of high wildlife value-in exchange for assured

community access to the rest of the Hemis National Park. It's a win-win deal.

The experience of other snow leopard range countries supports the

conclusion that sparse human presence does not affect this wild

cat's well-being. A soon-to-be published report on Mongolia by the

Seattle-based Snow Leopard Trust (SLT) indicates that the presence

or absence of nomadic herders around snow leopards inside as well

as outside PAs in the South Gobi Desert does not affect the

probability of snow leopards using a particular site.

Complementarily, there is no record anywhere in the world of a

human death due to a snow leopard attack.

So, by the time Project Snow Leopard drew up its plan in 2008, a

diverse team of officials and experts from the Union Ministry of

Environment & Forests, WII, WWF and NCF-SLT, apart from five

snow leopard states, had come to agree that 'given the widespread

occurrence of wildlife on common land, and the continued

traditional land use within PAs, wildlife management in the region

needs to be made participatory both within and outside PAs'.

More than one-third of the project budget (at least 3 per cent of the Ministry's total outlay) was earmarked for facilitating a 'landscape-

level approach', rationalising 'the existing PA network' and developing 'a framework for wildlife conservation outside PAs'.

Each of the five states was supposed to select a Project Snow Leopard site, a combination of PA and non-PA areas, within a year and set

up a state-level snow leopard conservation society with community participation. However, given the slow pace at which governments

function, not much has moved since, except in Himachal Pradesh, where the state forest department has set up a participatory

management plan for over half of Spiti wildlife division.

The red tape apart, two other factors are threatening to thwart this unique conservation project: the reluctance of the Ministry to

release funds to non-PAs, and the indifference of some state forest departments towards a management plan for areas outside

sanctuaries and national parks (such a plan must be submitted). "Snow leopards are present in many areas outside PAs, and I have

asked for proposals from all high-altitude divisions. But there is no response from the non-wildlife divisions yet. It's probably a mindset

issue," sighs Srikant Chandola, chief wildlife warden, Uttarakhand.

Perhaps the same mindset prompted a 2010 WWF-India report to recommend only PAs in Uttarakhand as potential sites for snow

leopard conservation, though the author Aishwarya Maheshwari now agrees that a landscape approach, "as mentioned in Project Snow

Leopard", is necessary.

Jagdish Kishwan, additional director-general (wildlife) at the Ministry, says that the Centre is keen to invest money in non-PAs, but

there are "some technical issues"; moreover, the Ministry's meagre allocation might end up too thinly spread in doing so.

The Ministry has its own grand recovery plan. Announced almost simultaneously with Project Snow Leopard, it has an ambitious Rs

800 crore scheme, Integrated Development of Wildlife Habitats (IDWH), aimed at the recovery of 15 key species including ones found

mostly outside PAs, such as: snow leopards, great Indian bustards and vultures. Centrally sponsored, IDWH has earmarked Rs 250

crore for 'protection of wildlife outside PAs'. The states have been asked to submit their Project Snow Leopard management plans under

the IDWH aegis.

If that is the case, what stops the Ministry from releasing money for non-PAs? "India's 650-odd PAs are our priority. But I agree that

certain key species need support outside PAs. We are examining these issues. The Government will find a way to provide funds to non-

wildlife divisions under Project Snow Leopard," assures Kishwan.

Going by the original 2008 document outlining the plan, Project Snow Leopard should have been in its second year of implementation

by now.

That it hasn't yet hit the ground, let's hope, is not a sign of apathy towards a big cat that has had-for no fault of its own-only a ghostly

presence in the consciousness of the establishment.

The author is an independent journalist

Cat Among The People

Snow leopards share a particularly punishing habitat with people in the higher reaches of the Himalayas, with resources

scarce and vegetation sparse. The conventional conservation model of separating wild animals and people simply does

not work here. India's green establishment is showing signs of accepting this reality, if only grudgingly

Jay Mazoomdaar | 30 July, 2010 | OPEN

So you know they are called 'ghosts of the mountain'. Rarely

spotted (they are as good as camouflage artists ever get), never

heard (the only one that ever roared was Tai Lung in Kung Fu

Panda, but then he was also nasty) and barely understood (few

behavioural studies have been attempted), they exist in smaller

numbers in India than even tigers.

But this is really not just about the most mysterious if not

charismatic of all big cats-snow leopards.

What you probably do not know is that the cat's natural habitat in

India is a 180,000 sq km expanse-nearly the size of Karnataka-of

Himalayan desert that spans the above-the-treeline reaches of five

states: Jammu & Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh,

Sikkim and Arunachal Pradesh. Cold and arid, this region is the

source of most north Indian rivers.

And yet, such a vast and critical expanse has rarely drawn the

attention of India's conservation establishment. On paper, there

exist more than two dozen Protected Areas (PAs)-sanctuaries and national parks-in this region, covering 32,000 sq km, a figure that

equals the combined area of all tiger reserves put together. But in terms of funds, staff and management, these high-altitude PAs are

mere markings on a map.

Things were worse in the early 1990s, when, as a young student of the Wildlife Institute of India (WII), Yash Veer Bhatnagar began

studying snow leopards and their species of prey. With sundry forest departments struggling to fill up field staff vacancies in the best of

India's tiger reserves, snow leopards had little hope of being watched over in places far less hospitable to humans. But as Bhatnagar

kept tracing the animal's tracks along Spiti's snow ridges, he grew increasingly restless thinking up a workable conservation strategy

that was proving to be as elusive as the big cat itself.

Nearly two decades on, Dr Bhatnagar and his associates would help shape Project Snow Leopard, a species recovery programme with an

innovative plan drafted in 2008 that could, with luck, save the species from extinction.

Dr Bhatnagar was not alone. His senior at the WII, Dr Raghu

Chundawat, having studied wildlife in the cold deserts of J&K since

the late 1980s, had already reported a startling fact: more than half

his subjects in Ladakh, including snow leopards, were found outside

the PAs. "There are a number of ecological factors behind this,"

explains Dr Chundawat, "sparse resources, extreme climatic

conditions, seasonal migration of prey species, etcetera, make the

cat very mobile across large ranges."

As for other efforts, in 1996, Dr Charudutt Mishra, another WII

alumnus and a snow leopard expert himself, had set up the Mysore-

based Nature Conservation Foundation (NCF) with a group of young

biologists. It had some valuable field experience to offer, too.

It was Dr Chundawat's work, however, that gave Project Snow

Leopard its broad direction. "Raghu's was a fantastic study and got

us thinking: 'If 80 per cent of Ladakh had wildlife value, how would

securing a few PAs help conservation?'" recalls Dr Bhatnagar.

The question still stands. Spiti in Himachal Pradesh is significant in terms of snow leopard presence, for example, but notifying all of

Spiti or Ladakh as a PA would not only be a logistical nightmare, given the difficulty in managing the existing PAs, but also defeat the

purpose of conservation on at least two counts.

First, the experience in other snow leopard-range countries shows that merely declaring vast areas as PAs does not help. In Central

Asia, for example, Tibet's Changthang Wildlife Preserve extends over 500,000 sq km, but organised hunting remains a serious threat in

most parts; the picture is not very different in Mongolia or Afghanistan.

Second, resources are extremely scarce at high altitudes; like the wildlife there, people must use every bit of land they can access at

those Himalayan heights. The conventional model of PA-based conservation demands the securing of inviolate spaces for wildlife. But,

in a cold desert, displacing people from existing PAs, leave alone notifying larger ones, amounts to threatening their survival. Besides,

can anything justify evicting people from PAs if wildlife is seen to coexist with people in non-PA areas?

But ten years ago, coexistence was too radical an idea to explore for much of India's conservation establishment.

In the absence of effective protection, what snow leopards once had

going for them was a sparse local population in the upper reaches of

the Himalayas (less than a person per sq km). In the past two

decades or so, however, even those heights have been witness to

'development' in the form of roads, dam projects and the like. The

most active government agency has been the military, busy

defending the country's borders, and, in the process, slicing and

dicing the region with impenetrable fences and encampments. All

this has also meant a labour influx, with whom indigenous

populations (and their livestock) now compete for natural

resources. This has meant overgrazing, and the competition for

resources has led to a loss of wild prey for snow leopards. And with

the big cats increasingly turning on livestock, they often face human

retaliation. Organised poaching has been a reality even here.

Clear that exclusive sanctuaries for snow leopards were not a

feasible idea, Bhatnagar and his colleagues focused on

understanding the cat and engaging with villagers and the local forest staff to figure out a conservation solution.

In 2001, the NCF's Mishra had done some groundwork in Spiti's Kibber Wildlife Sanctuary. Human communities, he found, could be

negotiated with to leave wildlife pastures untouched. To look after this area, a few villagers could be hired-picked by locals from among

themselves. This model has been in operation in Spiti for several years now, and so far, over 15 sq km has been freed of livestock grazing

around Kibber, and the population of bharals (blue sheep), staple prey for snow leopards, has almost trebled since.

Another coexistence success has been Ladakh's 3,000 sq km Hemis National Park, which is home to around 100 families that live in 17

small villages within it. Their relocation was impossible without subjecting them to destitution, since all the other land of Ladakh was

already occupied by either monasteries or local communities. Today, despite the human presence, Hemis has one of the country's

highest snow leopard densities. The park's villagers, urged by the Snow Leopard Conservancy India Trust (SLC-IT), an NGO, regulate

livestock grazing in pastures used by small Tibetan argali (a prime prey species for snow leopards). According to Radhika Kothari of

SLC-IT, this was achieved by the NGO in coordination with the forest department. They launched a sustained awareness drive and

offered families incentives such as home-stay tourism and improved corrals for the protection of their livestock.

The basic strategy of engaging local communities remains simple: help protect livestock (by ensuring better herding methods,

constructing corrals, offering vaccinations and so on), compensate for losses (via insurance, for example), create income opportunities

(community tourism, handicrafts, etcetera), restore traditional values of tolerance towards wildlife, and promote ecological awareness.

This story repeats itself in other range countries; livestock insurance and micro-credit schemes are big successes in Mongolia,

handicraft in Kyrgyzstan, and livestock vaccination in Pakistan.

Encouraged by early success stories in engaging local communities in J&K and Himachal, the NCF backed a conservation model in the

context of the three-decade-old Sloss debate (single large or several small, that is). "The idea of wildlife 'islands' surrounded by a 'sea'

of people does not work in high-altitude areas, where wildlife presence is almost continuous," explains Dr Bhatnagar, "Instead,

communities can voluntarily secure many small patches of very high wildlife value-small cores or breeding grounds spanning 10-100 sq

km each-if they have the incentive of escaping exclusionary laws across larger areas [big PAs]."

The NCF has identified 15 'small cores' in Spiti, of which three (at Kibber WLS, near Lossar, and near Chichim) have already been

secured through the foundation's efforts with locals. In Ladakh, too, village elders and the Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development

Council (LAHDC) agreed to stop grazing activities in seven side-valleys seen to be of high wildlife value-in exchange for assured

community access to the rest of the Hemis National Park. It's a win-win deal.

The experience of other snow leopard range countries supports the

conclusion that sparse human presence does not affect this wild

cat's well-being. A soon-to-be published report on Mongolia by the

Seattle-based Snow Leopard Trust (SLT) indicates that the presence

or absence of nomadic herders around snow leopards inside as well

as outside PAs in the South Gobi Desert does not affect the

probability of snow leopards using a particular site.

Complementarily, there is no record anywhere in the world of a

human death due to a snow leopard attack.

So, by the time Project Snow Leopard drew up its plan in 2008, a

diverse team of officials and experts from the Union Ministry of

Environment & Forests, WII, WWF and NCF-SLT, apart from five

snow leopard states, had come to agree that 'given the widespread

occurrence of wildlife on common land, and the continued

traditional land use within PAs, wildlife management in the region

needs to be made participatory both within and outside PAs'.

More than one-third of the project budget (at least 3 per cent of the Ministry's total outlay) was earmarked for facilitating a 'landscape-

level approach', rationalising 'the existing PA network' and developing 'a framework for wildlife conservation outside PAs'.

Each of the five states was supposed to select a Project Snow Leopard site, a combination of PA and non-PA areas, within a year and set

up a state-level snow leopard conservation society with community participation. However, given the slow pace at which governments

function, not much has moved since, except in Himachal Pradesh, where the state forest department has set up a participatory

management plan for over half of Spiti wildlife division.

The red tape apart, two other factors are threatening to thwart this unique conservation project: the reluctance of the Ministry to

release funds to non-PAs, and the indifference of some state forest departments towards a management plan for areas outside

sanctuaries and national parks (such a plan must be submitted). "Snow leopards are present in many areas outside PAs, and I have

asked for proposals from all high-altitude divisions. But there is no response from the non-wildlife divisions yet. It's probably a mindset

issue," sighs Srikant Chandola, chief wildlife warden, Uttarakhand.

Perhaps the same mindset prompted a 2010 WWF-India report to recommend only PAs in Uttarakhand as potential sites for snow

leopard conservation, though the author Aishwarya Maheshwari now agrees that a landscape approach, "as mentioned in Project Snow

Leopard", is necessary.

Jagdish Kishwan, additional director-general (wildlife) at the Ministry, says that the Centre is keen to invest money in non-PAs, but

there are "some technical issues"; moreover, the Ministry's meagre allocation might end up too thinly spread in doing so.

The Ministry has its own grand recovery plan. Announced almost simultaneously with Project Snow Leopard, it has an ambitious Rs

800 crore scheme, Integrated Development of Wildlife Habitats (IDWH), aimed at the recovery of 15 key species including ones found

mostly outside PAs, such as: snow leopards, great Indian bustards and vultures. Centrally sponsored, IDWH has earmarked Rs 250

crore for 'protection of wildlife outside PAs'. The states have been asked to submit their Project Snow Leopard management plans under

the IDWH aegis.

If that is the case, what stops the Ministry from releasing money for non-PAs? "India's 650-odd PAs are our priority. But I agree that

certain key species need support outside PAs. We are examining these issues. The Government will find a way to provide funds to non-

wildlife divisions under Project Snow Leopard," assures Kishwan.

Going by the original 2008 document outlining the plan, Project Snow Leopard should have been in its second year of implementation

by now.

That it hasn't yet hit the ground, let's hope, is not a sign of apathy towards a big cat that has had-for no fault of its own-only a ghostly

presence in the consciousness of the establishment.

The author is an independent journalist