forest rights, conservation and dilemmas of growth

forest rights, conservation and dilemmas of growth

© mazoomdaar 2011

© mazoomdaar 2011

Can’t get the Act together

The Left Front is the biggest advocate of the Forest Rights Act (FRA), but the legislation has been much abused under

the Left rule in north Bengal. Forest villagers dependent on tea garden jobs are indifferent to the Act. Families inside

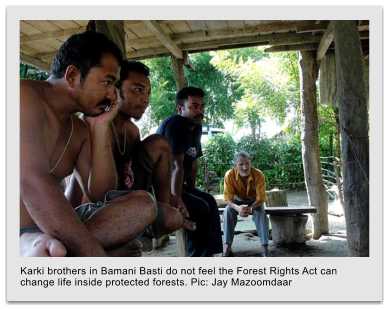

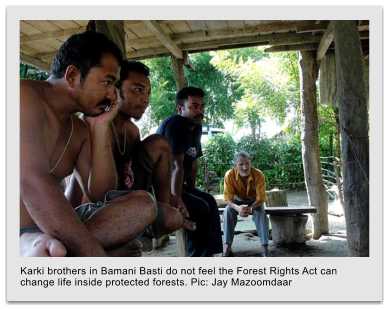

the Buxa tiger reserve are keen to surrender rights for Rs 10 lakh each. But away from tea gardens and outside the tiger

reserve, forest communities have bigger demands than the FRA allows. And a desperate forest department twists the Act

to retain control

Jay Mazoomdaar | 11 June, 2011 | OPEN

Jodi ektabodo hotel na koirte pari, patta-y ki labh (Of what use is this land title if I can’t

construct a big hotel here)?

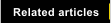

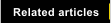

Not far from the forest office at Rajabhatkhawa in the buffer of the Buxa tiger reserve,

Gopal Sharma walks across his paddy field. Pampoo Basti got its name from a long

abandoned pump house. The 19 families settled here during the Raj for forestry work

have now multiplied to 44. Today, Sharma and his two brothers cultivate less than 3

acres in a forest fold. A minor change of course by a neighbourhood stream cost them

some land in 1993. Among them, the three brothers have eight children.

Sharma is a reasonable man. He walks, pointing out copious elephant droppings in wide

clearings of damaged crops, and pauses for a photograph or two. He does not hate the

herds. But the forest department, he points out, could have maintained the electric

fencing.

Villagers here have heard of the Forest Rights Act (FRA). But there is little excitement.

Sharma explains they have no future with such limited land holding and routine elephant

raids. Daily transport for good education and healthcare is expensive. So if the forest

department extends the Rs 10 lakh per family resettlement scheme to the buffer areas of

the tiger reserve, he would take the money and move on.

But why would he risk a new beginning when he is about to get his rights? For the first

time, Sharma sounds impatient: “What rights? I will still be tilling the same field, fight

the same elephants and stay in this hutment. How can we make a decent living in this forest? Yes, tourists do come here. But I can’t

even lease my land for a proper hotel.”

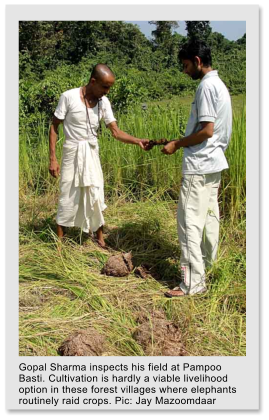

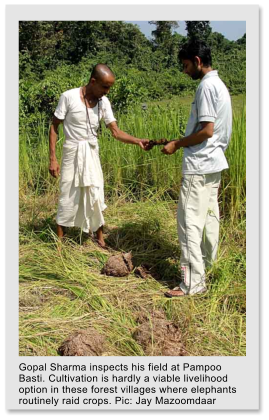

In neighbouring Bamani Basti, Darbahadur Karki describes an

aggressive herd of 80-odd elephants that gored two villagers a

couple of years back. The jumbos, he says, even raid their houses.

All 16 families here are eager to resettle if they get the Rs 10 lakh

package. “We have rights. We collect firewood. Our cattle graze in

the forest. We get compensation if leopards kill livestock. But is

this a life?”

It is the same refrain in Dalbadol, another forest village in the Buxa

buffer. Firewood apart, says Subir Chhetri, there is nothing much to

collect from the forest. Annual flooding drowns the fields for at

least three months, leaving layers of gravel on the soil. The villagers

might still break their back ploughing, laments Chhetri, were it not

for routine elephant raids. Soon, putting a cricket match on hold,

the village youth debate their chances of getting the resettlement

offer anytime soon.

Clearly, these forest villagers do not think that the FRA will change their life and Rs 10 lakh is a lot of money when their average

monthly family income does not exceed Rs 3000. But, with so many villagers so eager to move out, how many has the Buxa management

resettled so far?

Not a single one.

+++

Before conservation became a priority, one could take a train to the Bhutan border. Jayanti was a busy railway station transporting

dolomite and limestone. Now it is a large village inside the Buxa core that appears larger with a paramilitary camp and a forest

department campus. All that remains of the railway station is the canteen, since converted into a dhaba that serves jawans, forest staff

and the occasional tourist.

In 2008, the forest department conducted a survey here for

resettlement. By then, some villagers had set up rudimentary

tourist lodges on their properties. Quite a few vehicles and guides

were conducting jungle safaris around Jayanti. Barring these few,

the villagers were willing to move out.

But a gradual realignment of the Jayanti river has been threatening

the very existence of the village. Gravel flushed down has almost

filled up the riverbed. Each year, the monsoon surge shifts the river

towards the village. Eventually, people here would have no option

but to move out.

Before that could happen, Jayanti became a political battleground.

Villagers describe the flashpoint as a face-off between the “proxy-

Left” forest department and the local guides’ union that declared

allegiance to Trinamool Congress, the Left’s main political

opposition. Ostensibly to teach the guides’ union a lesson, the Buxa management flashed an advisory from the National Tiger

Conservation Authority (NTCA) for a gradual shift of tourism activities in all tiger reserves from core to buffer areas. The forest roads

around Jayanti were closed to tourists. The guides and drivers became jobless overnight. The lodges lost significant business.

What could have been a smooth resettlement has since become tense, with a section of the village leadership maligning the forest bosses

who, in turn, have denied even routine concessions, such as for boulder collection, to the villagers. The build-up to this atmosphere of

mistrust, however, began in 2009 with complaints of political partisanship.

In the Left manifesto for the 2009 general elections, the ruling parties claimed credit for backing the FRA in its present form. Even so,

Bengal was among the states where implementation of the Act was the most lackadaisical. The Left government in the state needed a

face-saver before the polls.

So party functionaries in North Bengal made the administration distribute some land titles in a hurry, without following the mandatory

democratic verification process. Not surprisingly, most of the pattas (land titles) were doled out in Left strongholds among party

sympathisers, many in tea garden areas.

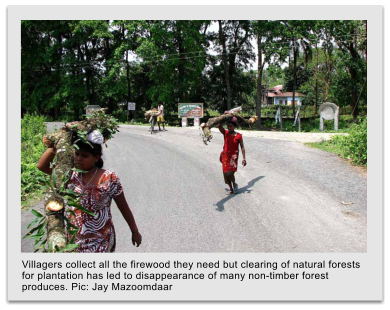

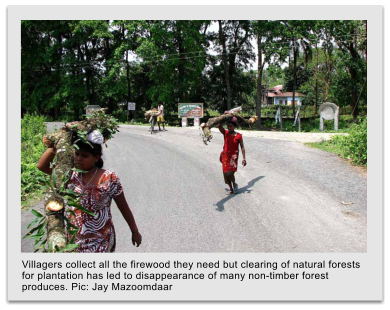

For example, all 287 families, mostly Ravas, in North Khaerbari got

land titles, 7-9 bighas each. Pukar Pradhan’s is one of the few

Nepalese families in the village. He says elephants do not venture

out to damage crops in this area (where forests are mostly

degraded) and the villagers are allowed to collect all the firewood

they need. Like Pradhan, many in North Khaerbari work at

Hashimara tea garden. Pradhan’s neighbour Gopi Rava says they

also get work under the government’s 100-day job scheme. Forest

rights have not made much of a difference to their life, but of

course, it is a “good thing to have land titles”.

Villagers at Jayanti, however, are not interested in pattas. Under

the FRA, non-scheduled tribes (non-STs) are required to furnish

proof of 75-year-residency (a tough ask anywhere) to claim rights.

More than 90 per cent of Jayanti’s population is non-ST. They

would rather move out immediately if the Buxa management offers

the resettlement package to all of them and if the money comes in a

maximum of two installments instead of the proposed five.

RP Saini, field director of Buxa tiger reserve, says the forest department is waiting for a 100 per cent consensus: “The process is on hold

due to the elections. But unless an entire village is shifted, the exercise will be futile. There are some elements who are trying to mislead

people. So we want the willing majority to convince those few who are still in two minds.”

Unless the political one-upmanship intensifies, it seems only a matter of time before villages from the Buxa core are moved out. Even

the villages in Buxa buffer may be offered the resettlement deal in the near future. But thousands of forest villagers outside the tiger

reserve will never have that option. And not all of them have access to tea garden jobs.

So they have other ideas.

+++

Organisations such as National Forum of Forest People and Forest Workers (NFFPFW) and North Eastern Society for Preservation of

Nature and Wild Life (NESPON) are mobilising forest villagers in this region to seek community control over forests under the FRA.

Such control, they argue, will give them the powers to manage and use forest resources in a sustainable way, like their forefathers did,

without any intervention from the forest department.

Forest villages, such as Kodal Basti in Chilapata, put up signposts in 2008, declaring the area as community forests. Subsequently,

villagers locked up the forest department’s timber yards, stopped clear felling of trees, and decreed that the forest department had no

authority to act without their permission. The department retaliated by demolishing the signposts and arresting a few villagers.

While the flare-up has somewhat eased in the past few months, the

tension, and a few questions, remain. Just how did the forefathers

of these forest villagers manage the forests? And do such practices

guarantee sustainable use of forest resources today?

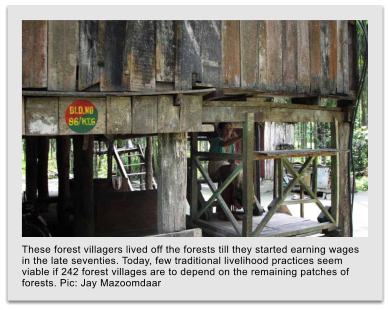

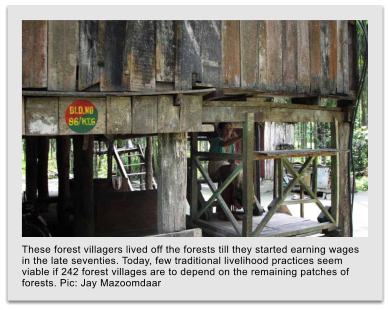

Across North Bengal, British foresters established forest villages

since 1910 as forced settlements of local communities such as the

Ravas, and outsiders Nepalese and Jharkhandis. These villagers

carried out forestry work, such as plantation and felling, without

any wages but were provided with homestead land and cultivable

plots. Their rights included collection of NTFP and firewood,

grazing cattle, cultivation of vegetables through inter cropping in

the plantations, fishing and regulated hunting.

Thus, forest villagers here completely lived off the forests till they

started earning wages in the late seventies. Around the same time,

the Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972 and the Forest (Conservation)

Act, 1980, came into being and many of their rights were compromised.Over the next few decades, wages became the prime source of

livelihood. Today, minimal forestry work means there is little opportunity to earn regular wages. Moreover, if the villagers intend to

control all work undertaken by the forest department, irrespective of the legitimacy of the demand, a hostile administration is not likely

to create jobs for them as firewatchers or guards.

Besides, few traditional livelihood practices seem viable if 242 forest villages are to depend on the remaining patches of forests.

Hunting is banned and fishing restricted. According to NFFPFW, growing focus on clearing natural forests and commercial plantations

over decades led to the disappearance of much of the NTFP. This also caused food scarcity for wild animals and pushed elephants to

raid crops more frequently. So leave alone vegetable inter cropping in the plantations, cultivation around the homesteads is not really

an option anymore.

Lal Singh Bhujel, who represents NFFPFW at Buxa, sums up the purpose of the “long struggle”. Once the communities have control over

these forests, they will shift the focus from commercial forestry and sustain themselves by restoring and conserving natural forests. But

this lofty pursuit finds no echo on the ground.

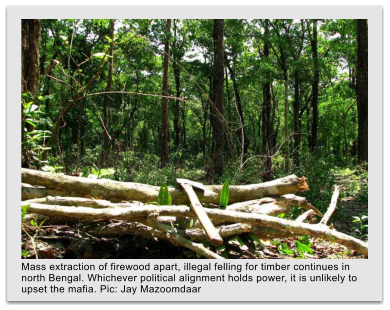

Less than 100 km from Buxa, Chilapata wildlife sanctuary is a tiny green patch in this fragmented forest landscape. One late morning, at

least 50 people are seen carrying green branches within a 5 km stretch. A thunder storm brought down many trees the previous night.

Otherwise, claims one of the fearless axe-wielders, there might not be half as many.

In Chilapata, about 230 families in Andu Basti, Kurmai Basti and Bania Basti are waiting for land titles. Last year, four families in Andu

Basti got lucky. Outside the youth club, Santosh Rava complains that a government survey has placed all the families in these forest

villages above poverty line (APL). This, he points out, when routine elephant raids do not allow anything more than a single crop of

paddy and NTFP means only some fruits and saplings.

Rava explains that villagers will apply for bank loans once they get

land titles: “With cash, one can try different options. We need good

irrigation and protection from elephants. Crackers and electric

fencing do not work. Irrigation canals may work as ditches. But

there are so many restrictions here. I could make about Rs 20,000 if

I was allowed to cut down one of these,” he points at a few surviving

old trees inside the village. But what happens when the trees are

gone? “We know all that… but we have to get by,” Rava walks away,

mumbling.

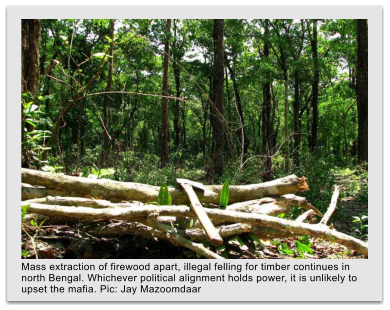

Formation of Forest Development Corporation (FDC) in the mid-

70s made forestry operations very lucrative. But already since the

1960s, collusion between a corrupt administration and the timber

mafia had cleared large tracts of forest in this region. While some

villagers made small fortunes on the fringe of this illegal economy,

many others were left out and have since been awaiting their turn.

Till a few years ago, many tea gardens here served bush meat to guests. In 2004, deer delicacies were still available at a few hours’

notice inside Buxa. Now, the impact is visible. Since nobody hunted bisons for meat, they are spilling out of pocket forests on the

highways. But it is difficult to spot deer in these forests.

Though commercial poaching seems to be under control now, the timber mafia has not given up yet. In 2008, two villagers died inside

Buxa when forest staff opened fire on groups who were allegedly felling trees. In this part of Bengal, where people and institutions never

cared much for wildlife and forest laws, an interpretation of the FRA in terms of complete community control over forest resources for

sustainable use does not sound too reassuring.

On its part, the forest department is desperate to retain control. Forest villages here came under the Panchayat system in 1996 but the

forest department got to control the development funds. Today, the department promptly suspends all development work in villages

that challenge its authority. When it came to settlement of rights, the administration did not even bother to convene a single gram

sansad meeting and violated provisions of the FRA while selecting members for forest rights committees (FRCs). In December 2008, the

state even issued a new circular on joint forest management, restricting forest rights to “usufructs” controlled by the forest department,

that too outside Protected Areas.

When NGOs, such as NFFPFW, objected to these violations of the FRA, the administration dubbed them as “disruptive forces” and

branded local rights activists as Maoists. In 2010, top officials of Buxa tiger reserve warned this reporter, who had met local NFFPFW

functionaries, that the administration tapped all phone conversations of those who “entertain anti-national elements” as evidence.

Amid such administrative paranoia, the political parties are mostly

silent. Even during the state elections this April, while all local

candidates had a lot to promise the tea garden workers, a huge

constituency that can swing results, no outfit, not even Akhil

Bharatiya Adivasi Vikas Parishad, talked about implementation of

the FRA.

In the nearest town, Alipurduar, says a young timber merchant on

condition of anonymity: “Whichever political alignment holds

power, it is unlikely to upset the traditional equations. Kono change

paba na (you will see no change). Today, the mafia keeps the

(forest) department and one set of political bosses happy.

Tomorrow, they might be paying another set of politicians and, if

this new Act really rolls out, some community strongmen.”

Caught in this political blind spot between the administration and

the activists, most forest villagers here are wary of their future.

Sitting in his rickety, wooden quarter, Dhanbahadur Chhetri does not

understand the fuss about a new Act that will soon make Pampoo Basti a revenue village. Under which law, wonders the octogenarian,

did Station Para become a revenue village when a few retired railway staff set up the colony in 2005 right inside the Rajabhatkhawa

forest?

“Rules and laws are for the powerful. So everyone is fighting for power. There is no middle ground here, no future for the poor,” says the

old man, retiring to his room. His time is up, but Chhetri will not stop his two sons if they get enough money to buy some land away

from the forest.

Mazoomdaar is an independent journalist

Home | Reports | Related Articles | Resources | Gallery | Feedback | Contact | About

Home | Reports | Related Articles | Resources | Gallery | Feedback | Contact | About

Home | Reports | Related Articles | Resources | Gallery | Feedback | Contact | About

Home | Reports | Related Articles | Resources | Gallery | Feedback | Contact | About