forest rights, conservation and dilemmas of growth

forest rights, conservation and dilemmas of growth

© mazoomdaar 2011

© mazoomdaar 2011

The great iron ore heist

The Posco project in Orissa is not just about violation of people’s rights and a green disaster. It is easily the biggest loot

of India’s natural wealth. It is also the most brazen example of how the country’s who’s who are colluding to mock the

rule of law

Jay Mazoomdaar | June 16, 2011 | Abridged in OPEN

East India Company pori Posco amo oopore shaasan koriba payeen

ethare aasi pahanchichhi (Like the East India Company, Posco has

come here to rule over us).

More than a hundred armed police personnel lined up on the

narrow Balitutha bridge that connects the proposed Posco site to

the rest of the state. Less than a hundred yards away, around a

thousand angry villagers stood ground. They rallied here, man and

woman, from the affected villages to protest the land acquisition

drive, under the banner of Posco Pratirodh Sangram Samiti (PPSS).

This was May 18. The day the state government resumed the land

acquisition process, nine months after it was put on hold by

Environment and Forests minister Jairam Ramesh in August 2010.

Two weeks ago, Ramesh lifted the stop work order. Soon, the forces

marched in with revenue officials.

As six families surrendered betel vines for cash compensation in Polang village some 15 km away, animated Left leaders addressed a

rally at Balitutha. CPI-M state secretary Janardan Pati dared the administration to risk a bloodbath, and his CPI counterpart Dibakar

Nayak vowed not to allow Posco to do an East India Company in Orissa. It was past noon, temperature scaling the 44 degree mark, and

not a shade in sight. But a reflexive crowd roared in response.

Two days ago, at a four-bench roadside eatery in Erasama, around 20 km from Balitutha, Tamil Pradhan was wolfing down a very late

lunch. Vice-president of the United Action Committee (UAC) and the most visible face of the pro-Posco community leadership,

Pradhan had just finished a marathon meeting where the UAC placed six conditions before the district administration for land

acquisition.

As his cellphone rang incessantly, Pradhan sounded naively confident that the administration would not resume land acquisition

without taking the UAC into confidence. “Let them first decide on our demands. They need our support against the PPSS to enter the

area.”

“We are not for or against any factory,” he thundered between two fistfuls of rice. “People did not invite Posco here. So if they want the

factory, they will have to give people their due. But all these anti-Posco elements have selfish agendas. Soon after the MoU (between

the state and Posco) was signed in 2005, (CPI leader) D Raja came here to back his party cadres and attacked Posco as a blacklisted

multinational, equating it with the East India Company.”

In six years, the rhetoric has not changed. But the fate of this Rs 52,000-crore FDI cannot be decided on rhetoric but hard facts. And

hard facts tell a damning story that rarely surfaces above the media log of the many dubious milestones of this prolonged back-and-

forth.

THE PASS

From Noida in Uttar Pradesh to Jaitapur in Maharashtra, land acquisition is always an emotive issue. So much so that the collapse of

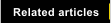

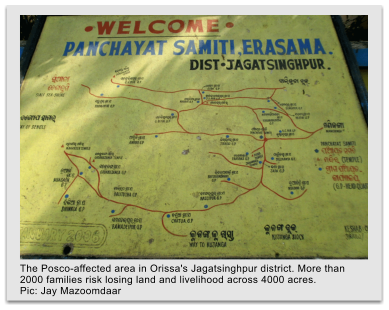

the Red bastion in West Bengal is being largely attributed to the Left’s disastrous bid to take over land for industry. Posco’s case is still

more sensitive. Since 3,097 hectares out of the 4,004-acre proposed Posco project area is classified as forest land, Posco required

environmental clearance for land diversion.

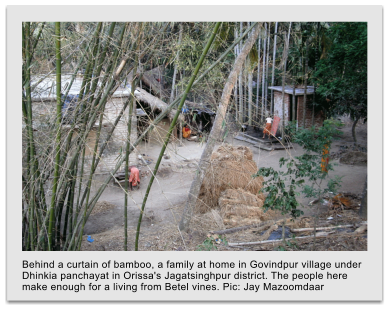

Standing on Balitutha bridge, however, one cannot spot any trace of forest in the horizon leading to the bay of Bengal. While the pro-

Posco camp contests the forest land status, pointing out that people here got farming loans from the government in the early 1980s,

those opposed to the steel plant furnish British records dating back to 1928 to claim how the area was always recorded as “dense

deciduous forest where people grew betel”.

The forest has disappeared since. Betel vines, arguably the country’s finest, and paddy fields have taken over much of the land. So in

August 2008, the Supreme Court offered “in principle” clearance for diversion of “forest land” for the Posco plant, hinging it on the

MoEF ensuring compliance to all relevant laws.

The Forest Rights Act (FRA) had come into force in January 2008, empowering forest dwellers to determine the nature and extent of

land use for non-forestry work. Another year passed in protests and rhetoric. Meanwhile, the UPA was re-elected to power and Jairam

Ramesh took over as minister of environment and forests. In August 2009, he ordered that no application for land diversion for Posco

could be made without the consent of the gram sabhas affected.

On record, not a single paper moved in the next five months between the state and the MoEF regarding the consent of these gram

sabhas. Yet, Ramesh granted the “final clearance” for land diversion on December 29, 2010, in violation of his own August 2009 order.

But following nationwide outrage, the minister had to issue a clarification in 10 days flat. On January 8, 2010, he wrote to the state

that “final clearance” was “conditional” on settlement of rights under the FRA.

What followed was surreal (See Shame). Ignoring the resolutions passed by the gram sabhas, Orissa claimed that there were no tribals

or traditional forest dwellers in the project area. In the months to follow, two government-appointed committees –under N C Saxena

and Meena Gupta – nailed the state government’s lies. Following the first report that questioned the implementation of the FRA, the

MoEF stopped land acquisition in August 2010. Based on the second report – that called the state’s claims “false” and “fabricated” --

the Forest Advisory Committee (FAC) on November 19, 2010, recommended temporary withdrawal of the forest clearance.

Ignoring these recommendations, on January 31 this year, Ramesh offered yet another “conditional” final clearance. The project was on

if the Orissa government could give an “assurance” that there were no “eligible persons” for FRA in the area. The state government sent

the “assurance”, repeating all the claims earlier trashed as “false” by the government inquiry panels.

Meanwhile, village Forest Rights Committees had filed a complaint with the MoEF and passed fresh resolutions, rejecting consent for

diversion of land. Ramesh sought the state’s response to these resolutions. The Orissa government on April 29 termed the palli sabhas

illegal, the resolutions fake, and said the sarpanch had “overstepped the jurisdiction vested in him and misutilised his official

position”.

So on May 2, keeping “faith…in what the state government says”, Ramesh accorded the final approval for land diversion, adding some

safeguard clauses (See Safety myths). To cover his back, the minister added that he expected that the state would “immediately pursue

action” against the sarpanch for what it categorically said were “fraudulent” acts, and, “if no action is taken forthwith, I believe that the

state government’s arguments will be called into serious question.”

Sisir Mahapatra, sarpanch of Dhinkia, was suspended on May 27 but no case has been filed against him yet. Mahapatra says he will

move the Orissa High Court to contest the suspension.

THE POLITICS

After his hurried lunch, UAC’s Tamil Pradhan blamed an Indian

steel giant for fuelling the anti-Posco movement and drove away in

a silver Indigo to his house in Nuagaon to freshen up before

dashing off to a TV studio in Cuttack. Pradhan’s neighbour, UAC

chief Anadi Raut, is a retired headmaster. He orders a cold drink

on his terrace and sounds quietly confident: “We are giving

conditional support to Posco. So they (Posco and the

administration) have to accept our terms because these PPSS

people oppose the plant unconditionally.”

Raut’s brother-in-law Dr Damodar Raut is a Biju Janata Dal

veteran. An inter-party power tussle recently cost the MLA from

Erasama the agriculture portfolio. Many credit Dr Raut with the

pro-Posco UAC movement but he is sulking: “From 38 per cent in

1948, Orissa’s forest cover is down to 14 per cent. All our forests

are being mined. We need land for agriculture but we are blindly

going for industry. The state has signed 49 MoUs for steel plants and another 27 for power.”

But wasn’t he the man chief minister Naveen Patnaik entrusted with breaking the anti-Posco resistance? Dr Raut nods grimly: “Yes, the

CM asked me to use my good offices to reach out to the affected villagers. We made good ground. But now I am keeping away as things

have taken a different turn. The Posco MoU expired last year. How can the state acquire land without renewing the MoU, without a

proper rehab package?”

PPSS spokesperson Prashant Paikray finds Dr Raut’s “new stance” amusing. At his modest Bhubaneswar home, he goes through his

media routine and furnishes every detail to prove that villagers in the project area met all conditions to be eligible under the FRA

(see Rights wronged). Asked if the PPSS was indeed sponsored by Posco’s competitors, as alleged by UAC’s Pradhan, Paikray laughs.

He cut his teeth as a rights activist in Gopalpur, he recalls, fighting Tata Steel’s SEZ project. Then he goes back to his media routine

again.

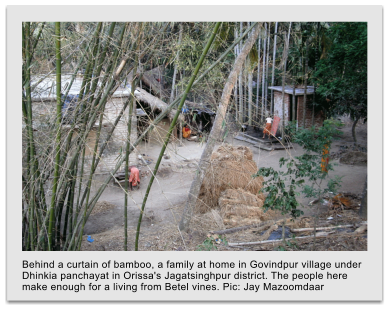

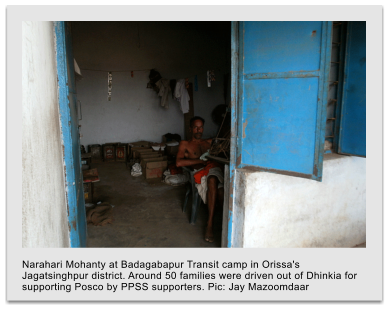

On way to Balitutha, hollow faces stare at outsiders from a small refugee camp by the road. This is Posco Transit Camp where around

50 families stay put in one-room tenements under tin roofs, sharing nine “common” toilets. They are from Patana, a Dhinkia

neighbourhood, the heart of the anti-Posco resistance. In June 2007, they apparently refused to vote for the Left candidate backed by

the PPSS. So they say they were tortured and driven out of the village.

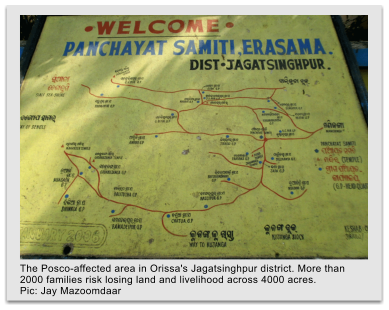

Like his neighbours in Dhinkia, Narahari Mohanty used to make Rs 10-12,000 a month from his betel vines. Now he has converted a

window of his sweltering, one-room hutment into a stationery shop that does not sell items worth Rs 20 a day. “Who will buy? We have

become paupers overnight,” he rues. Mohanty has seven family members to feed and the Rs 600 monthly refugee allowance has not

been coming for three long months. The camp youth gather around silently. Sangram Parihar says none of them has a job. Do they

regret supporting Posco? Parihar turns away and whispers to his friend Santosh Mohanty who decides against confiding in a stranger.

In Dhinkia, roads are the obvious casualty. No government agency could enter the village in years, not even the PWD. Off non-existent

roads, it takes a kilometre’s walk across sand dunes from Gopalpur to find CPI leader Abhay Sahu, who controls the PPSS, in a

casuarina grove. His siesta interrupted, Sahu takes questions lying on a cot under a cashewnut tree.

“Why even bother to term our gram sabhas illegal and signatures fake if we don’t qualify for the FRA? They (administration) had to lie

because they know that people are living here for generations. Okay, our gram sabha is illegal, but where is the legal gram sabha? They

say we (the PPSS) misguide people. why don’t they hold a free and fair gram sabha with independent observers and take a vote?” Sahu

smiles like a man in control.

So who funds the PPSS? Sahu says many organisations support them in solidarity. Besides, every villager contributes one rupee per

betel plant – not much, explains Sahu, considering a single betel leaf fetches the same in the market. But is the PPSS coercive? Sahu

frowns: “If you are talking of those families who were paid by Posco to conspire against fellow villagers, I will say people have shown

restraint to let them leave the village unharmed.”

With the same panache, he dismisses charges that he has too many properties to his name for a fulltime politician. “These charges

make me more famous,” Sahu’s smile returns. He smugly informs that he carries on 46 court cases, his wife has a government job and

his sons are both engineers. Then he excuses himself to prepare for the next day’s big rally against a possible resumption of land

acquisition.

THE GROUND

The next day, May 18, as forces lined up to take on a possible PPSS

onslaught at Balitutha, Nuagaon sarpanch Bhaskar Swain was busy

weighing out flour in his grocery shop. Both the PPSS and UAC

leadership winced at the mention of his name. Swain was candid

that he switched sides frequently: “I found that both sides have

vested interests. The UAC only want good deals for their members.

The PPSS has a political agenda. I want every villager to benefit.

For that, all three panchayats should sit together.” Swain poses for

a quick photo before returning to the waiting customers.

At Balitutha, additional superintendent of police (Paradip) SK Das

said he has enough reserve forces to deal with the PPSS rally if it

“turns ugly”. Given the charges of police atrocities in the past, did

presence of the media worry him? Das sounded philosophical: “We

are not demons; we do not use force on peaceful protest.” Soon, the

PPSS rally stopped a hundred metres short of the police formation, roared to fiery speeches by its leaders, and dispersed in a few

hours. A relieved Das waved at a few friendly press photographers as they drive back.

Things remained largely peaceful during the next week as the administration acquired land from villagers “willing” to accept cash

compensation. But the “willing” were few and soon the forces joined the action. People, among them elected gram panchayat members,

were forced to accept “compensation” and even detained if they resisted destruction of their betel vines.

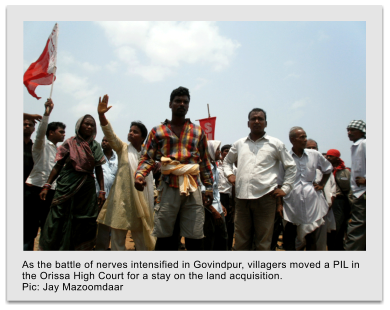

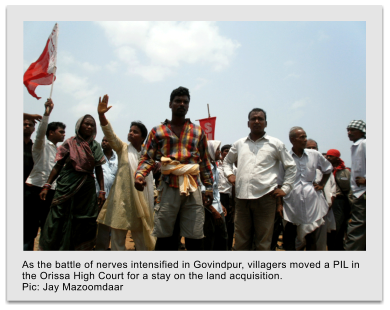

So, at the heart of anti-Posco resistance, villagers of Govindpur and Dhinkia put up human barricades. Under a scorching sun,

children and women of Govindpur and Dhinkia villages lay on roasting sand to form two human rings, blocking approach roads.

Unable to persuade the defiant villagers, the team sneaked in from the seaside on June 11. The daily bulletin proudly proclaimed that

the government had taken over 24 betel vines. What went unreported: villagers rebuilt the vines the next day and women and children,

back to take turns under the sun.

The miffed UAC leadership, meanwhile, has been reined in by the administration with an assurance that its demands will be considered

soon (much to the relief of Pradhan, who besides his UAC commitments, now has to take time out for the ongoing Orissa Premier

League, an IPL-format Twenty20 cricket tournament in which he has “some stake”).

As the battle of nerves intensified in Govindpur, villagers moved a PIL in the Orissa High Court on May 20 for a stay on the land

acquisition. The next hearing is on June 20. National Board for Wildlife member Biswajit Mohanty also moved the high court against

the state for allotting ports to private parties through direct negotiation, without inviting public bids as mandated by the Centre. While

the petition will be heard again on June 21, an interim order on May 30 barred the state from signing any MoU for private ports

without the court’s permission, in effect, stalling Orissa’s plan to ink a fresh MoU (the one signed in 2005 expired last year) with

Posco.

THE LOOT

While India pats itself on netting the single largest FDI, Posco is

poised to make many times its investment from iron ore only. The

2005 MoU allows the Korean company to extract 600 MT iron ore

over 30 years. Orissa’s 2004 MoU with Tata Steel allowed

extraction of just 250 MT ore for a 6 MTPA steel plant at

Kalinganagar. Clearly, Posco got to extract an extra 100 MT ore for

its 12 MTPA plant.

Why does Posco need so much iron ore? Because the company

always wanted to export ore (10 MT per year) and the 2005 MoU

allows it to ship out 30 per cent of the ore it extracts. In fact, the

2005 MoU also concedes that Posco may source an additional 400

MT of iron ore from India for their steel plants in Korea through a

long–term supply arrangement from the open market. There is a

fat margin between the domestic open market (average Rs

4400/tonne) and the international price (average Rs 7400/tonne) of iron ore. For 400 MT, it adds up to Rs 1.20 lakh crore.

Posco gets this deal at a time when the national consensus is moving towards limiting iron ore export to help the domestic steel

industry. India is the world’s largest iron ore exporter after Australia and Brazil. But in terms of per capita reserve, India has only 21

tonnes of iron ore against Brazil’s 333 tonnes and Australia’s 2000 tonnes. Various studies have estimated that business-as-usual will

exhaust Indian’s iron ore reserve anytime between 2025 and 2040.

Karnataka banned iron ore export in 2010, Chhattisgarh is considering the option and Orissa chief minister Naveen Patnaik’s own Steel

and Mines Minister Raghunath Mohanty floated a similar proposal this January. Even Ramesh, while issuing the final clearance to

Posco on May 2, hoped that “the new MoU would be negotiated by the state government in such a way that exports of iron ore are

completely avoided”.

Exports apart, the financial implication of subsidising 600 MT iron ore for a multinational is grave. The state governments earned a

paltry Rs 27 per tonne till the Centre fixed 10 per cent of the domestic market price (Rs 4,400/tonne for high quality ore in Orissa) as

revenue in 2009. The same iron ore fetches an average price of Rs 7400 in the international market. Discounting for royalty and

operation cost (mining, freight etc), the margin stands at around Rs 6,200 per tonne.

So, if Posco bought the allotted 600 million tonnes of ore in the international market, the company would have to shell out an

additional Rs 3.72 lakh crore. That is India’s gift to a Korean competitor, a scam much bigger than the 2G mobile spectrum allocations

worth around Rs 1.76 lakh crore. Even if Posco bought the same quantity of ore at the domestic price (average Rs 4400/ton) for the

Orissa plant, it would still have to spend an extra Rs 1.92 lakh crore. And, iron ore price will keep soaring. It has risen by more than

500 per cent in the past 30 years.

Obviously, Indian buyers will have to pay international price for steel from Posco’s Orissa plant. Besides, the Posco project got an in-

principle approval as a Special Economic Zone (SEZ) in 2006. The SEZ status means that the Centre and the Orissa government will

have to forfeit bulk of the projected revenue of Rs 89,000 crore and Rs 22,500 crore, respectively, as tax sops.

Moreover, Posco’s SEZ status (read free export zone) and the captive port will make it very difficult for the authorities to keep a tab on

how much ore Posco ships out from its exclusive facilities. Since the government levies no export duty in SEZs, it will also be much

more profitable for Posco to export its steel produce from Odisha than to sell it in the domestic market.

Not all developing nations dump their national interest so casually. Posco tried the same deal in Brazil in 2004 when it inked a pact

with Companhia Vale do Rio Doce (CVRD) for setting up a steel plant at the port city of Sao Luis and sourcing cheap ore from the

Carajas mine. But CVRD not only insisted that Posco buy ore at market price but also hiked the 2004 price of ore by 71 per cent in

2005.

So Posco shifted focus to Orissa.

THE PLOY

Aware of India’s strict green laws, Posco, very methodically, first

broke down its mega plans into segments and then downplayed

each component to obtain clearances. The company’s controversial

acquisition of 4004 acres is for the port and the power-cum-steel

plant only. The project requires another 8100 acre land – 6,100

acre (mostly forest) for mining and 2000 acres for two townships

at the steel plant and the mine.

The proposal for the power-cum-steel plant itself is misleading.

The application for environmental clearance mentions a 4 MTPA

steel plant and not the 12 MTPA that will come up in just 6 years.

The environmental impact of the power plant was considered for

only 400 MW installed capacity and not the entire 1100 MW that

would follow.

The primary requirement of a steel plant: iron ore. Posco is yet to get permission to mine 6,100 acres of lush forest in Kandadhar Hills

to extract those 600 million tonnes of ore. On July 14, 2010, the state high court cancelled the out-of-turn allotment of mining permit

to the Korean MNC. In October, the state government moved the apex court against the HC order and the matter is sub judice.

The second key requirement: water. It is not clear if the approval for fresh water use of 10 million gallon daily (MGD) -- slashed from

the original approval for 16.5 MGD -- is meant for the 4 MTPA production level or the full 12 MTPA-level. In 2006, Posco got

permission to draw 125 cusec water from the Jobra barrage. Following protests by the Mahanadi Banchao Andolan, backed by the

Bharatiya Janata Party, the state asked Posco in September 2010 to draw water from Hansua river instead. While the company has

commissioned a fresh feasibility study, the issue remains unresolved.

Without any certainty on securing ore and water, Posco has frog-leaped to acquire land for its plant. And the final component – a port

to ship produce – is the first unit they got cleared; but again, not without doctoring facts. The captive port was proposed as a minor

port to escape the stringent reviews that major ports attract. But the Posco port will construct two massive breakwaters – one 1070-

metre-long to the north and another 1600-metres-long to the south – to control turbulence. There will be a 13-km-long approach

channel, with a minimum width of 250m, to allow 170,000 DWT ships, among the biggest in the business.

Clearly, Posco’s Orissa plot is larger than the sum of its parts. Getting started with the port and plant before obtaining rights to ore and

water is an attempt to force a fait accompli, a phrase Ramesh himself uses liberally to describe the Navi Mumbai airport, Jaitapur

nuclear plant or coal blocks across India.

Not that everyone was blind. In November 2007, the Supreme Court’s Central Empowered Committee (CEC) in its report noted that

“instead of piecemeal diversion of forest land for the project, it would be appropriate that the total forest land required for the project,

including for mining, is assessed and a decision for diversion of forest land is taken for the entire forest land”. In fact, the SC’s in-

principle approval in August 2008 to diversion of 3,093 acre forest land for the Posco plant shared these concerns.

But the MoEF was not listening.

THE PUSH

Ramesh’s leap of faith is not out of sync with the alacrity shown by

his predecessors in the green ministry in pushing the Posco

project. But were they under pressure from their bosses and

colleagues in the government?

Consider these:

•

In 2007, a file noting on May 8 shows the Finance Ministry

sought an update on the Posco project. The next day, a letter

from the Director, Disinvestment, wanted the status of the

Posco proposal to be sent to the Finance Ministry by May 18

as then Finance Minister P Chidambaram was meeting the

members of the Investment Commission on May 24.

Within days, a few hours before he relinquished charge at

the MoEF to take over Telecom on May 16, A Raja issued the

environment clearance to Posco port, probably the last of 2,016 green clearances he granted in just 36 months.

•

Again in 2007, a letter dated June 4 from the Finance Ministry sought the status of the Posco applications by June 11, for a

review meeting on the project’s progress was scheduled for June 16. The MoEF expert appraisal committee (EAC) cleared the

plant at its meeting on June 20.

The majority in the Meena Gupta inquiry committee noted that “the proximity of the dates between the letters from the Finance

Ministry and the hasty processing of the approvals by the MoEF and the EAC despite the serious shortcoming and illegalities is

more than a mere coincidence” and “the brazen interference of the Ministry of Finance into functioning of another Ministry is

most unfortunate, highly improper and against public interest”.

•

Meena Gupta took charge as MoEF secretary on June 1, 2007. Since Raja had already moved to Telecom, MoEF was effectively

under the Prime Minister’s Office. Posco had applied for port clearance in September 2006 and it took Raja eight months to okay

it. The application for environmental clearance for the Posco plant was filed on April 27, 2007. Under the PMO, Gupta issued the

clearance on July 19, in less than three months. Again, when the Orissa government sought clearance for diverting 3000 acre

forest land for the plant on June 26, 2007, Gupta promptly obtained an in-principle nod from the ministry’s FAC on August 9,

2007.

•

Could it be a coincidence that Ramesh handpicked the same Meena Gupta to head the four-member fact-finding committee in

2010? Unsurprisingly, Gupta was the lone dissenter in the panel and found nothing wrong with the clearance for land diversion

that she had issued herself.

•

Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, along with Orissa chief minister Naveen Patnaik, assured South Korean President Lee Myung-

bak about speedy clearance of the Posco project when the latter was in New Delhi as the chief guest for the Republic Day parade

last year. Minister of Steel Virbhadra Singh even offered a 6-month deadline for handover of land to the Posco delegation that

accompanied the Korean President.

Dr Singh repeated the assurance at the 17th ASEAN summit at Hanoi last October. During the G20 summit at Seoul last November,

India’s Ambassador to South Korea S R Tayal said there was “a common desire on both sides to see the project through” and “every

effort is being made by all stakeholders”.

It is surprising how the cream of the Indian administration, from the Prime Minister to an Ambassador, could offer personal

commitments on an issue to be decided on its legal merit. Evidently, the pressure on MoEF to clear the project before G20 was

enormous. After failing to meet the deadline, Ramesh blamed the FAC for delaying its report and assured the who’s who in the power

circle that “the decision will be taken within a couple of weeks”.

Eventually, it took Ramesh a few months to mock the FAC, sundry committees of his own making and the rule of law to clear Posco

with a lofty justification: “Beyond a point, the bona fides of a democratically elected state government cannot always be questioned by

the Centre”. But can the bona fides of a democratically elected gram panchayat be questioned any more than that of a state

government?

For the villagers of Dhinkia, it may be too late for an answer.

Mazoomdaar is an independent journalist

Home | Reports | Related Articles | Resources | Gallery | Feedback | Contact | About

Home | Reports | Related Articles | Resources | Gallery | Feedback | Contact | About

Home | Reports | Related Articles | Resources | Gallery | Feedback | Contact | About

Home | Reports | Related Articles | Resources | Gallery | Feedback | Contact | About